Mental Models: How to Think Clearly in a Complex World

Have you ever watched someone solve a seemingly impossible problem with ease and wondered, "How did they see that when I couldn't?" Or perhaps you've admired how certain people consistently make better decisions across diverse situations. Chances are, they're wielding what might be the most underrated intellectual superpower available to us: mental models.

I've always been fascinated how top performers across fields—from business titans to scientific pioneers—approach complex problems. The pattern is unmistakable. The most successful thinkers don't just know more; they think differently. They use mental models.

What Are Mental Models (And Why Should You Care)?

Mental models are frameworks that help us understand how things work. They're conceptual tools that simplify complex systems into understandable, usable forms. Think of them as cognitive shortcuts that help you navigate reality without having to figure everything out from scratch each time.

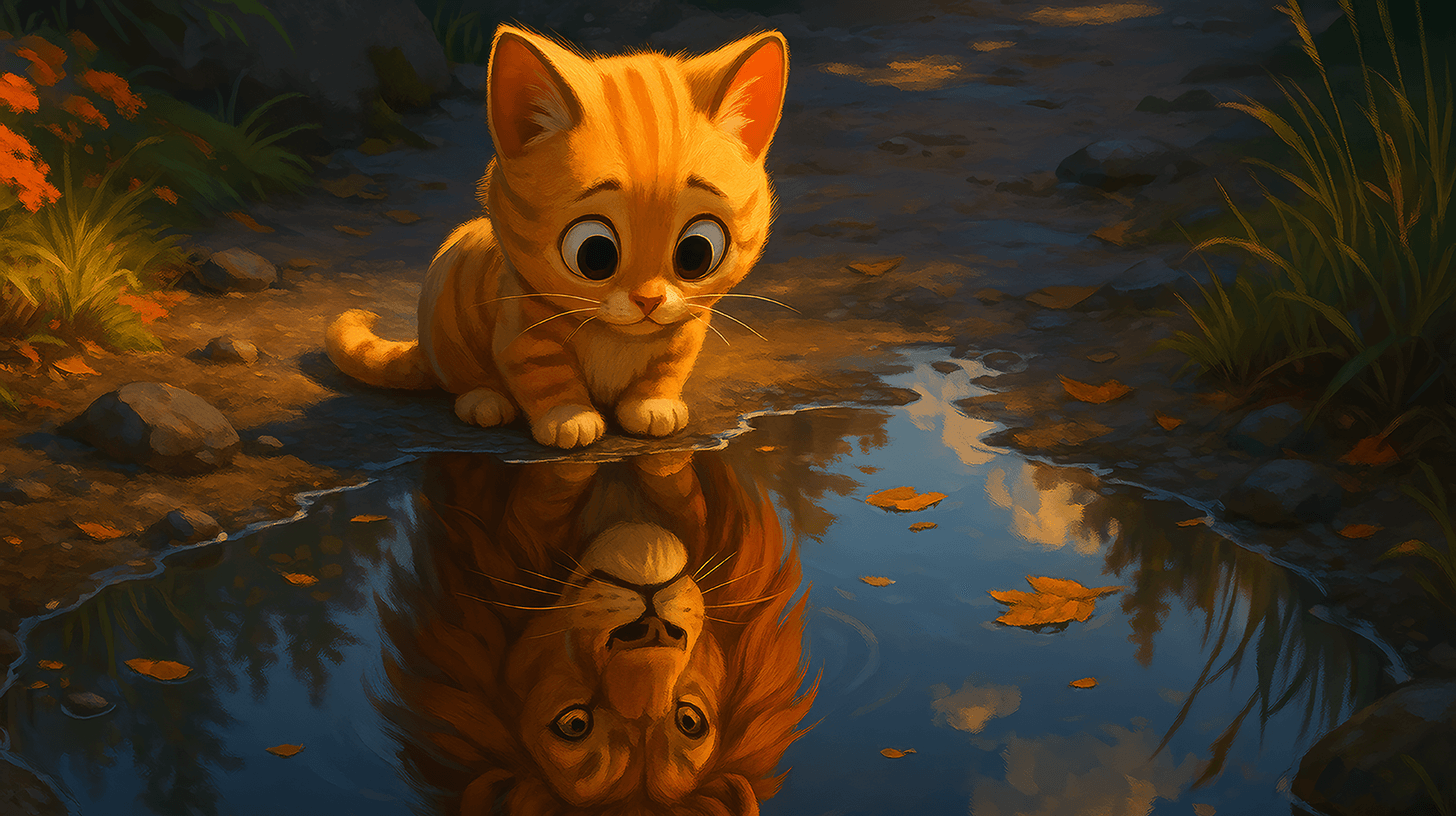

The real magic happens when you collect and connect diverse mental models. Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett's business partner and an advocate for this approach, calls it building a "latticework of mental models." When you have only one or two models, you're intellectually vulnerable—like trying to build furniture with only a hammer.

As Munger puts it: "To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail."

Most of us unconsciously rely on a handful of models from our education or profession. Engineers think in systems and feedback loops. Economists see incentives and trade-offs everywhere. Psychologists notice cognitive biases and behavioral patterns.

But what if you could think like all of them when the situation calls for it?

The Five Mental Models That Will Transform Your Thinking

Let's explore five particularly powerful models that can revolutionize how you approach problems:

1. First Principles Thinking: Breaking Down Reality to Its Fundamentals

Most of us reason by analogy—we look at what others have done and make incremental improvements. First principles thinking does the opposite: it breaks problems down to their fundamental truths and builds solutions from there.

When Elon Musk tackled space travel, he didn't ask, "How can we make existing rockets marginally better?" Instead, he asked, "What are rockets fundamentally made of, and what's the theoretical minimum cost of those materials?" This approach led to SpaceX cutting launch costs by over 70%.

How to apply it:

- When tackling a problem, ask yourself: "What are the irreducible fundamental truths in this situation?"

- Question assumptions by repeatedly asking "Why?" until you reach bedrock principles

- Build your solution up from these fundamentals rather than copying existing approaches

2. Inversion: Solving Problems Backward

Want to be successful? Great—but have you identified what would guarantee failure and how to avoid it?

Inversion flips problems on their head. Instead of asking, "How do I achieve X?" you ask, "What would guarantee I fail to achieve X?" Then avoid those things.

This approach—deeply embedded in Stoic philosophy and mathematics—often reveals insights that forward thinking misses. Avoiding stupidity is easier than achieving brilliance.

How to apply it:

- When planning a project, create a "pre-mortem": list everything that could cause it to fail

- For personal development, ask not just what habits would make you successful, but what habits would definitely make you fail

- Before important decisions, consider: "What would be the worst possible choice here, and why?"

3. Second-Order Thinking: Playing Chess, Not Checkers

First-order thinking considers immediate outcomes: "If I do X, Y will happen."

Second-order thinking goes further: "If I do X and Y happens, what happens next? And after that?"

Most people stop at first-order consequences, which is why so many solutions create bigger problems than they solve. Diet pills that cause worse health problems. Quick fixes that create dependencies. Short-term gains that lead to long-term disasters.

Consider how Netflix initially lost subscribers when raising prices in 2011—a negative first-order effect. But the increased revenue funded better content, ultimately attracting millions more subscribers—a powerful second-order effect that short-term thinkers missed.

How to apply it:

- Before making decisions, explicitly map out consequences beyond the immediate outcome

- Ask: "And then what? And what might happen because of that?"

- Look for systems where short-term pain leads to long-term gain (or vice versa)

4. Probabilistic Thinking: Embracing Uncertainty

We crave certainty in an uncertain world. Our brains evolved to create coherent stories and make confident predictions—even when the evidence doesn't warrant it.

Probabilistic thinking embraces uncertainty by thinking in ranges and probabilities rather than absolutes. It's why weather forecasts say "70% chance of rain" rather than making binary predictions.

This model is essential for navigating complex systems where perfect prediction is impossible: markets, relationships, careers, and more.

How to apply it:

- Express confidence in ranges rather than absolutes: "I'm 70% confident this will work"

- Create multiple scenarios with different probabilities when planning

- Recognize that being wrong is often not a failure of judgment but the inevitable result of dealing with probabilistic systems

5. Opportunity Cost: Every "Yes" Is a "No" To Something Else

Every choice you make isn't just about what you're doing—it's also about what you're giving up. The opportunity cost model reminds us that resources (time, money, attention) spent on one option are no longer available for other options.

This mindset transforms decision-making. That "bargain" purchase isn't such a bargain if it prevents you from buying something more valuable later. That "quick meeting" isn't so quick when you consider what you could have created in that time instead.

How to apply it:

- Before saying yes, ask: "What am I saying no to by accepting this?"

- For major commitments, create an explicit list of what you'll have to give up

- Establish an "opportunity cost threshold"—a minimum return an activity must provide to be worth your time

The Multiplier Effect: Why Mental Models Are Stronger Together

Here's where the true power emerges: when you apply multiple models to the same problem.

Consider a career decision:

- First principles thinking helps you identify what truly matters to you fundamentally

- Inversion helps you avoid career paths doomed to make you miserable

- Second-order thinking reveals how an initially challenging job might open doors later

- Probabilistic thinking helps you weigh uncertainties realistically

- Opportunity cost thinking ensures you consider what alternatives you're giving up

No single model gives you the complete picture. But together, they provide a robust framework for making a wise choice.

Building Your Mental Model Collection: A Practical Approach

Creating your personal latticework of mental models doesn't happen overnight, but here's how to start:

-

Begin with breadth over depth

- Familiarize yourself with models from various disciplines: psychology, economics, mathematics, biology, physics, etc.

- Resources like "Poor Charlie's Almanack," "The Great Mental Models" series, and "Farnam Street Blog" are excellent starting points

-

Practice deliberate application

- When facing a decision or problem, consciously select 2-3 models that might apply

- Journal which models you used and how effective they were

- Review periodically to see which models consistently provide value

-

Study the masters

- Find thinkers known for interdisciplinary thinking and study their approach

- Notice how they combine models from different domains to solve problems

-

Teach others

- Explaining mental models to someone else deepens your understanding

- Try explaining how you used mental models to solve a problem

Remember: the goal isn't to collect models like trophies but to develop flexible thinking that deploys the right models at the right time.

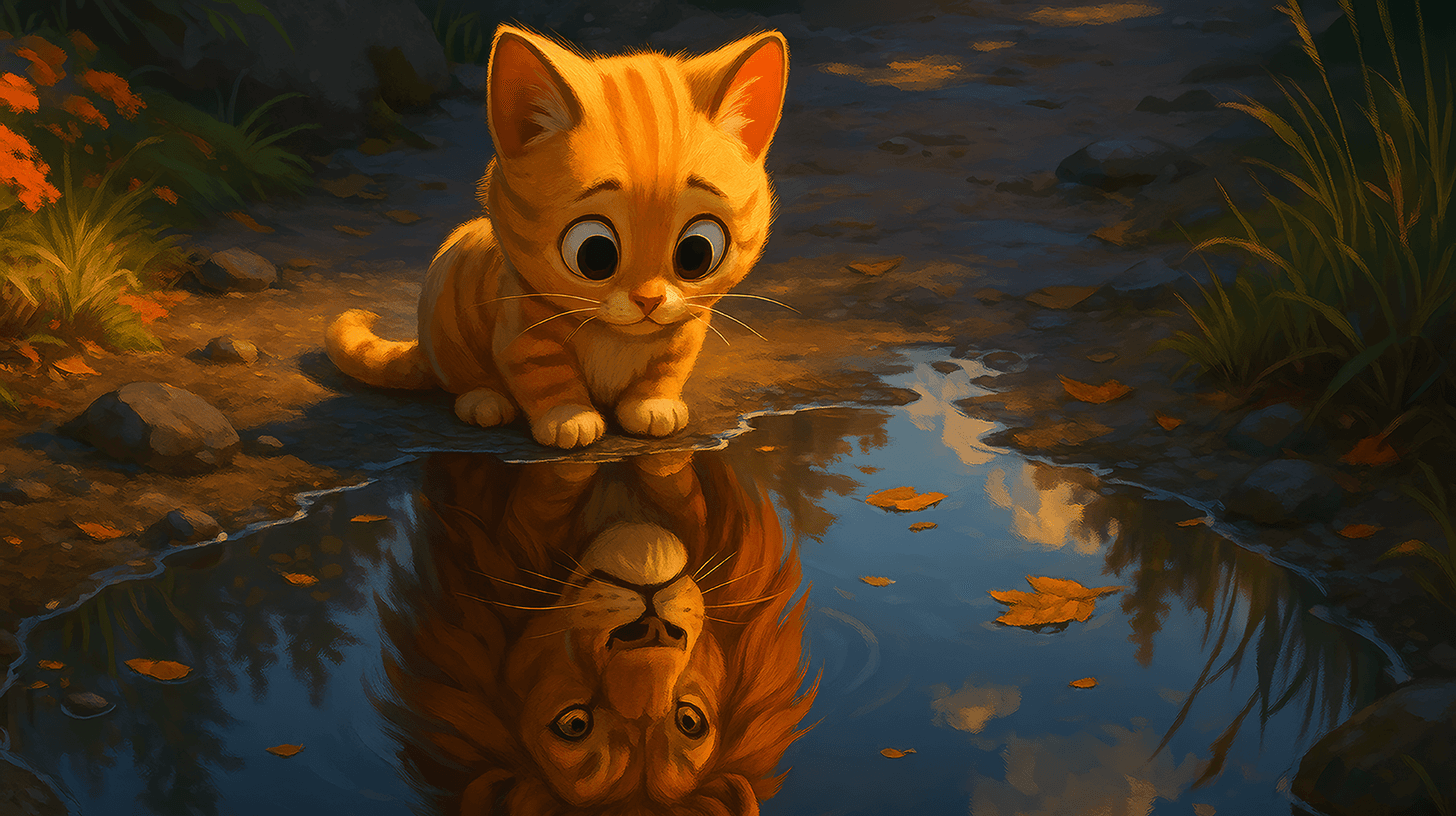

A Final Thought: The Meta-Mental Model

Perhaps the most valuable mental model is what we might call the "meta-mental model"—the recognition that all models have limitations. As statistician George Box famously said, "All models are wrong, but some are useful."

The world is more complex than any model can fully capture. True wisdom comes from knowing which model to apply, when to apply it, and when to set it aside for a different perspective.

By building your latticework of mental models, you're not just accumulating knowledge—you're developing wisdom. You're training yourself to see reality more clearly from multiple angles, to avoid common pitfalls, and to find solutions others miss.

In a world of increasing complexity and information overload, this might be the ultimate competitive advantage.

What mental model will you add to your toolkit first?